In 2025, it’s a typical experience to step into a café, order a flat white, and hear barista ask “regular milk or…?”.

Personally, I’m a dairy milk girl. I know it can be a little controversial, but I grew up on semi-skimmed cow’s milk— from my Nesquik bottles in the mornings, to my overly sugared coffees as a teen, and now my daily flat whites. Cow’s milk has always been my default.

But in 2020, when I moved to the UK for university and began living with people from different parts of the world (not just my family members), I quickly realized I was the odd one out. In a house of five girls, I was the only one who still drank cow’s milk. Our fridge looked like a line-up of milk alternatives from Sainsbury’s: semi-skimmed, soy, two oatly cartons, and almond milk

As I went through university and later started working, I kept wondering: is this just a lifestyle choice—or are there real health, cultural, and environmental reasons behind what milk we reach for?

The Rise of Plant-Based Milks

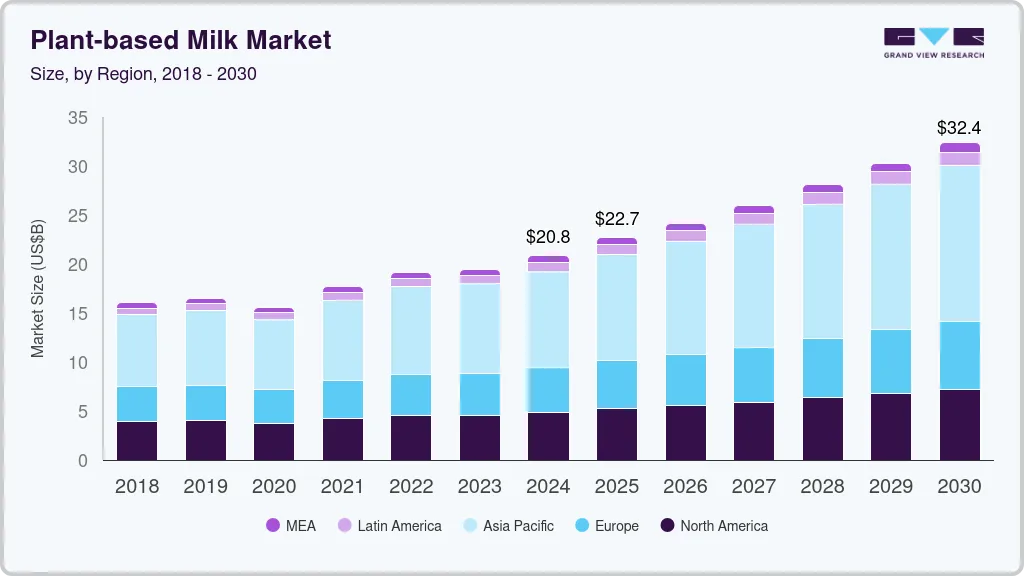

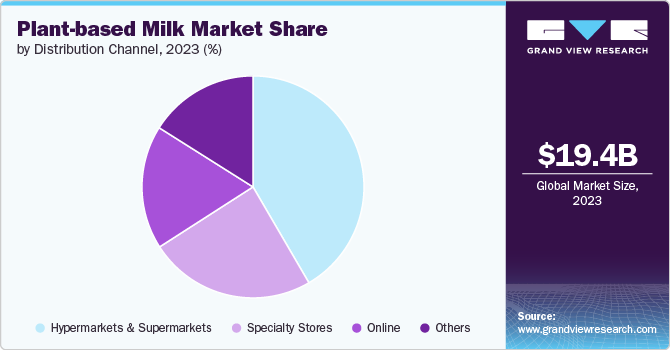

We’ve all seen the increase of plant-based milks all over, from coffee shops to supermarkets and even in the office. The growth of plant-based alternatives in the western market has grown substantially, with the current profit standing at $19.42 billion in 2023 and is forecasted to grow to $32.35 billion by 2030 (Grand View Research, 2024).

But in many parts of the world, these alternatives have been around for centuries. Soy milk has been used in East Asian countries, including China, Japan and Korea, a lot, often consumed warm for breakfast. But why is this common practice in these cultures and not in the west? Well, it all comes down to history, culture, environment, and genetics.

East Asia isn’t traditionally very well suited for large-scale cattle dairying—limited pastureland in densely populated areas results in fewer cows per family compared to Europe’s open grasslands. In China, for example, soybeans have been cultivated for thousands of years (since at least 1000 BCE). And the use of soy products, such as tofu, soy sauce, soy milk, became staple protein sources long before dairy could have been. As for soy milk, its earliest forms are tied to tofu production: after soaking, grinding, and straining soybeans (to get what amounts to soy milk), people would curdle the liquid to make tofu. (Hymowitz et al.,1970).

On the contrary, in South Asia (India, Pakistan, and Nepal) dairy is tightly woven into everyday cuisine and religious life. Cow’s milk and buffalo milk are widely used to make paneer, yogurt and sweet desserts. For much of Europe, archaeological evidence shows that Neolithic communities were already turning milk into cheese and yoghurt around 7,000 years ago. However, in North Africa and the Middle East, where temperatures can reach above 40 °C, goat and sheep milk are common. Often fermented into Laban or kefir to make them last longer in hot climates; in these areas milk is as much cultural identity as nutrition.

So, if milk is everywhere — from lassi in India to kefir in Morocco — why can some people drink it daily, while others struggle after a single glass? The answer isn’t just cultural. It’s biological.

Lactose Intolerance & Lactase Persistence

On top of cultural and geographical reasons, genetics plays a huge role in the milk we chose to pick up. Whether or not you are able to drink a latte or have some cheese without running to the bathroom, all depends on one enzyme: lactase.

My dad drank cow’s milk happily for decades but started feeling lactose intolerant symptoms in his 50s. What changed? The answer lies in our genes, specifically whether your body keeps producing the enzyme lactase after childhood. In big-picture thinking, humans are not actually ‘designed’ to drink milk as adults. In most mammals, the gene for lactase switches “off” after weaning. Only in some human populations genetic mutations arose that kept the lactase gene (LCT) switched “on” throughout adulthood. This is called lactase persistence (Gerbault et al., 2011).

In East Asia about 90% of adults are lactose intolerant, compared with fewer than 10–30% in much of Europe. This isn’t about dietary choice, it’s about whether you carry the LCT gene (Storhaug et al., 2017). This is one of my favourite examples of gene-culture co-evolution: when early farming communities in Northern Europe began relying heavily on cow’s milk as a food source, those who could drink it without discomfort had a clear advantage. The digestion of milk allowed for more calories in lean times, a steady supply of protein and fat, and a safe alternative to contaminated water. Over generations, this meant the lactase-persistence trait spread widely through the population. In contrast, in regions where fresh milk was never a common food, there was no such pressure — instead, soybeans and other staples became the key source of protein and the foundation of survival.

Sustainability & Generational Changes

The boom of increased use of plant-based alternative milks in Europe isn’t just about health or lactose intolerance — it’s about the planet. Producing a litre of cow’s milk uses around 628 litres of water and nearly 9 square meters of land, while oat and soy milks need less than a tenth of that space and as little as 28–48 litres of water per litre. On top of that, dairy milk creates about three times more greenhouse gas emissionsthan most plant-based options. Almond milk does use more water than other alternatives, but still comes out with a lower carbon footprint than cow’s milk. It’s easy to see why younger generations, who are often more eco-conscious, are reaching for oat or soy in their lattes.

But it’s not only about sustainability. Younger generations are driving much of the shift: a 2024 UK study found that adults aged 24–39 reported significantly higher consumption of plant-based foods, with many citing social media and advertising as major influences on their choices (MDPI, 2024). Migration also plays a role, and research shows that when people move, they bring their own food traditions with them while also adopting new ones from the culture around them. (ScienceDirect, 2025). This leads to blended and combined food and drink habits, that shift people’s perceptions, mix traditions, and adapt diets in ways that feel both global and personal.

At the end of the day, whether you are team dairy or team plant-based, milk is more than just what’s in your cup; it’s a story of culture, science, and choice.

Leave a comment