Introduction

Have you ever thought to yourself “I’d love to be stronger, but I really don’t want that bulky look”? If so, you’re definitely not alone — I’ve thought it too. It’s a phrase I’ve heard countless times from friends, at the gym and across social media. But where does this misconception actually come from? And why are women still so afraid of muscle?

Well, there are a few main reasons behind this misconception. First, there’s a biological misunderstanding of how muscle growth actually works in women compared with men. Then there’s the historical fitness culture that still shapes how we think about exercise today, reinforcing media stereotypes and social conditioning around what women’s bodies “should” look like. Together, these factors have convinced many women that strength training is a “male” domain and that if you choose to do it, you’ll inevitably become bulky or be perceived as masculine.

Part 1: The Physiology of Muscle and Why Gender Isn’t the Barrier We Think

This misconception arises from a blanket misunderstanding of biology, specifically, how muscle growth works, and it’s not the fault of the individual. It’s the result of decades of misinformation built into our education systems, media and fitness culture. Most people assume that lifting weights automatically means getting bigger — but that’s not really how it works, especially for women.

The process of building muscle, called hypertrophy, works the same for everyone and is an evolutionary mechanism to adapt to muscle stress. When you perform resistance training, you create tiny amounts of mechanical tension and microscopic damage to your muscle fibers. Your body then repairs those fibers through a process called muscle protein synthesis, where new proteins are built to reinforce and thicken the muscle tissue. Over time, this cycle of damage and repair makes the fibers stronger and more resilient, hence growing that muscle. After a workout, muscle protein synthesis remains elevated for roughly 24 to 48 hours, depending on factors like training intensity, nutrition and sleep. To build muscle, your rate of synthesis needs to outpace muscle protein breakdown, hence why both training and diet matter.

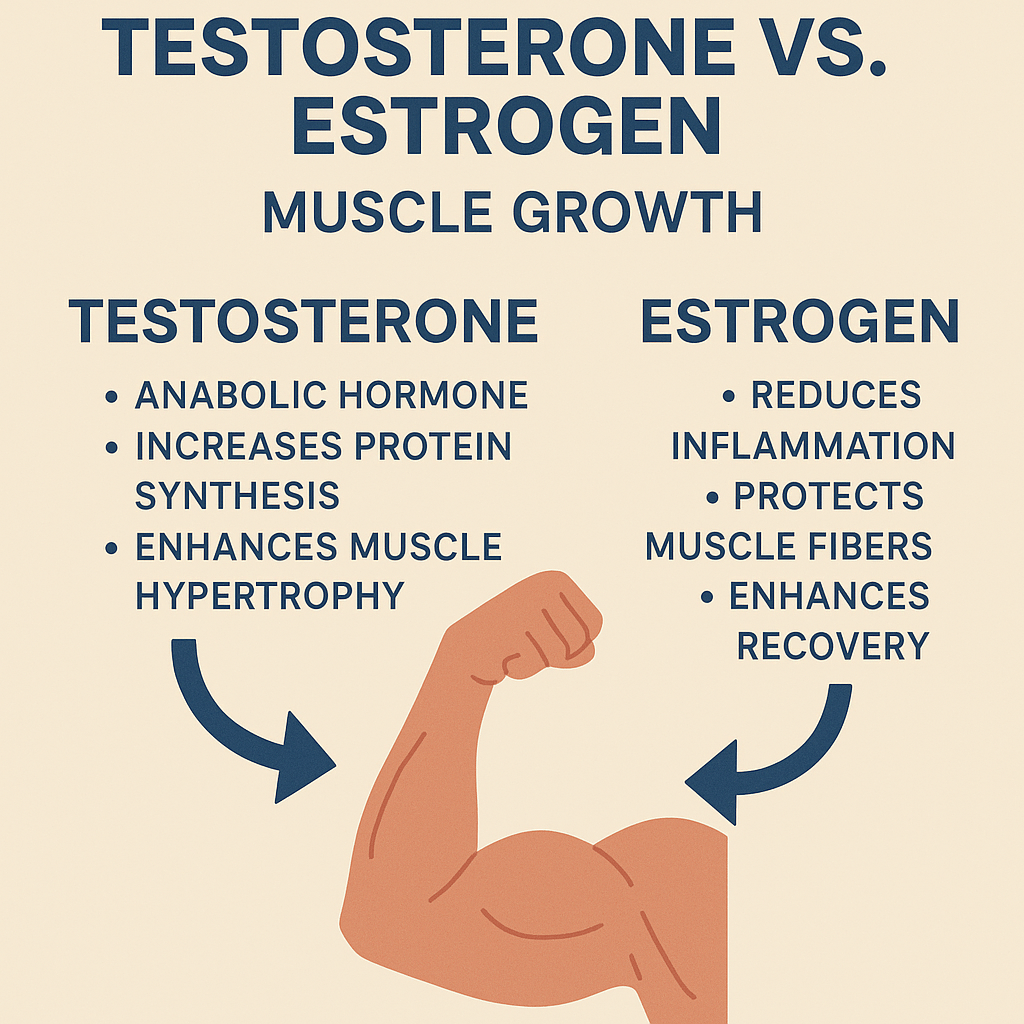

While the biological process of hypertrophy is identical in men and women, hormones influence its magnitude. Men’s have 10 to 20 times more testosterone than women, which enhances protein synthesis, leading to faster or more visible muscle growth. Women, on the other hand, benefit from the protective effects of estrogen: the primary female sex hormone responsible for regulating the menstrual cycle, reproductive function and secondary sexual characteristics such as fat distribution and breast development. Estrogen helps reduce inflammation, limit muscle damage as well as improve recovery and regeneration. So, while testosterone promotes faster muscle growth, estrogen supports the resilience and endurance of muscle tissue, hence why women often recover more efficiently and experience less post-exercise soreness. With lower testosterone and higher estrogen, women’s muscle growth tends to occur more gradually and with smaller overall increases in size. This doesn’t mean women can’t build visible muscle, only that it requires a higher training and nutritional support to reach the same degree of hypertrophy. That’s why lifting weights a few times a week won’t suddenly make anyone “huge”, it takes deliberate, progressive training for muscle size to develop noticeably.

The takeaway is simple: biology isn’t what’s holding women in the gym back— misinformation is.Somewhere between the lab, the fitness classes and the marketing world, “getting strong” was rebranded as something women should fear instead of embrace. So, ladies, grab those weights, you’ll build strength, confidence and power, not a Hulk-sized frame.

Part 2: The history of women’s fitness

While it’s easy to blame education and misinformation for not explaining the biological differences between men and women within exercise, the root issue stems from centuries of societal standards, gender norms and cultural practices. Long before we understood physiology, ideas of what women should look like were already firmly established.

In the Victorian era and early 19th century, women’s health advice was centred on delicacy, softness and fragility. This was mainly due to the idea that exercise was believed to threaten fertility and the female organs. Doctors often promoted the “conservation of female energy” theory, which is the idea that women should avoid exertion and preserve their energy for reproductive function. This belief shaped medicine, culture, and even pop culture; films and period dramas often show women being told to rest, stay in bed, or refrain from movement, especially during pregnancy.

By the 1930s-1960s, the modern “physical culture” movement exploded, led by figures like Eugene Sandow and Jack LaLanne. Strength and muscle development became a symbol of masculinity and national pride. Women, however, were urged into fitness programmes focused on charm, pose, posture and beauty. Women who lifted weights were portrayed as oddities or “unfeminine” in magazines and public exhibitions. Muscle continued to be a male-coded trait. Gyms finally began to be marketed to both men and women, although in very different manners. Driven by commercial opportunity, women were still advertised “long and lean” exercises, lots of cardio and generally avoid weights. Fonda’s aerobics videos became iconic, but they also reinforced the idea that women’s fitness was about shrinking, toning, and burning calories. This period created the word “tone” as a gendered alternative to “strong”, a way to market exercise to women without implying muscularity. Towards the end of the 20th century, the dominant be beauty standard was extremely thin rather than strong and athletic. Spot-reduction myths, fat-burning zones, and “slimming workouts” were everywhere and strength training was still culturally coded as masculine.

Finally, around the 2010s the narrative began to shift. Social media introduced far more visibility of women training, lifting weights and performing at high levels, not just for aesthetics but for strength and passion. Evidence-based fitness became mainstream and scientifically, myths like “bulking” were scientifically debunked. Still, older beliefs persist, especially among older generations, traditional gyms and people influenced by decades of outdated fitness messaging.

Part 3: The gap in the research

Although it may seem on the surface that women and men are now included equally in sport and exercise, this still isn’t the case. Recent analyses show that only around 6% of sports and exercise science research focuses exclusively on women, despite women making up roughly half of all participants in sport and physical activity. Women have been historically excluded from scientific research, particularly in fields rooted in military needs. Early exercise science emerged from military training programmes during WWI and WWII and these programmes were built entirely around male soldiers. Research priorities, therefore, were centred on male physiology, endurance, strength and performance. As a result, the foundational norms of fitness research were based almost exclusively on male bodies.

Throughout most of the 20th century, women were excluded from clinical trials due to the belief that their hormones made them “too variable” to study. Researchers saw menstrual cycles as a confounding variable, as opposed to an intrinsic characteristic. This created a self-fulfilling gap: we won’t study women because we don’t understand them, and we won’t understand them because we won’t study them.

Part 4: The Conclusion

Despite progress, modern day exercise science is still overwhelmingly based on male data. This causes a domino-effect of misunderstandings: from female-related injuries to training programs that fail to account for female metabolic and hormonal differences. The belief that women “get bulky” wasn’t created by biology; it was created by history. Outdated gender norms, biased research and decades of misleading marketing shaped a narrative that has nothing to do with how female bodies actually work. Modern evidence shows that women benefit enormously from strength training, physically, hormonally and physiologically. The future of women’s fitness cannot, and will not, continue supporting this outdated narrative.

References

Handelsman et al., Endocrine Reviews, 2018

Schoenfeld, J Strength Cond Res, 2010, PMID: 20847704

Hubal et al., J Appl Physiol, 2005, PMID: 15531562

Handelsman et al., Endocr Rev, 2018

Tiidus, Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 2013, PMID: 23038262

Vertinsky, P. The Eternally Wounded Woman. Uni of Ill Press, 1994.

Chapman, D. Sandow the Magnificent: Uni of Ill Press, 1994.

Dworkin, S: Gender, Health, and the Selling of Fitness. NYU Press, 2009.

Alperin, A. Social Media’s Role in Normalizing Muscular Women. J of Health Com, 2020

Tipton, C. M. History of Exercise Physiology. Human Kinetics, 2014.

Bekker et al. Sex differences in research design. BMC Women’s Health. 2007

Costello et al., “Where are the females in sports and exercise medicine research?” British Journal of Sports Medicine (2014).

Leave a comment